Famed for his “Iron Triangle” theory of health economics, University of Pennsylvania Professor William Kissick was a larger-than-life figure who played a major role in both early federal Medicare policy-making and in shaping Penn’s Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics (LDI), the first academic center dedicated to multidisciplinary health economics and policy research.

“He was like Forrest Gump or Woody Allen’s Zelig,” remembered Professor Arnold Rosoff of the Wharton School. Rosoff was one of many University of Pennsylvania faculty members who worked with Kissick, who retired in 2001 after 32 years of teaching as a professor in three separate health-related Penn Schools. Kissick died in 2013.

Thick of the action

“He seemed always to have been in the thick of the action when something big happened,” said Rosoff, “Mention a significant milestone in the evolution of the U.S. health care system and Kissick was there — in the second row of the crowd, standing close behind Wilbur Cohen and LBJ when Medicare was signed, for example. He was clearly made of the stuff that Tom Brokaw styled as ‘the greatest generation.'”

Kissick is one of the LDI-connected health services research and policy pioneers being spotlighted as part of the Institute’s 50th Anniversary in 2017.

Prior to joining Penn and LDI in 1968, Kissick, who held four degrees from Yale, first came to national attention as an academic whiz kid in a seven year stint with the federal government. There, along with other White House assignments, he was one of two physicians on a small team that wrote what became the 1965 law establishing Medicare. And for the rest of his professional life, he remained a nationally renowned expert on health care policy.

Changing Penn

After his role in the back-office policy work that launched the most sweeping changes in the history of American health care, Kissick moved to Penn and immediately began changing that institution as well.

He was recruited to Penn in 1968 by Robert Eilers, a Wharton School Professor of Insurance and LDI Executive Director who was leading one of the first university efforts to establish interdisciplinary scholarship initiatives focused on both the medical science and business management of health care. This was triggered by the launch of Medicare and the realization that new sorts of research were needed to fill fundamental gaps in the evidence base essential to making informed policy decisions about the organization, management, financing and delivery of health care on such a large scale.

Toward that interdisciplinary goal and funded by a $4 million gift from Leonard Davis, the CEO of the Colonial Penn Insurance Group, Wharton had established the Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics (LDI). Simultaneously, and in a move that set a new national academic precedent, the incoming Kissick was named to professorships in both Penn’s School of Medicine and The Wharton School of business, and named to LDI’s governing board.

Launching Health Care Management program

Rosoff remembered that Kissick and Eilers “shared the same vision and fed each other’s egos and enthusiasm” for the groundbreaking project. Within two years, LDI had organized and launched the Wharton Health Care Management Program — a curriculum designed to produce, among other things, graduates who had both MD and MBA degrees.

Wharton Professor Mark Pauly, a nationally-renowned health economist and long-time Kissick colleague who would himself later serve as executive director LDI for five years, said that against the odds, LDI and the Health Care Management Program “flowered and flourished” under Kissick’s aegis. “Without Bill’s presence and expert guidance, either organization could easily have been cut up in academic infighting and power politics.”

LDI has since grown into one of the largest academic institutions of its kind — a hub of health-related research conducting by more than 200 Senior Fellows across the faculties of six Penn schools and Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP).

“Bill Kissick,” said Wharton and Penn Perelman Medical School professor J. Sanford Schwartz, “was inherently interdisciplinary and a leader in the effort to link Wharton, the social sciences and medicine together in the educational and training process.”

Team that established LDI

Schwartz, who would later serve for nine years as LDI executive director, remembered that, “Kissick played a pivotal role with four others who were the team that established LDI and led it with great skill for decades.” The other four were Eilers; Willis Winn, then-Wharton Dean; Samuel Martin, professor and founding director of the Robert Wood Johnson Clinical Scholars Program; and Dan McGill, then-Professor and Chair of Wharton’s Insurance and Risk Management Department.

“Beyond LDI,” Schwartz said, “Kissick brought health policy into the medical school curriculum. I remember as a medical student in 1970, a group of us were interested in the social sciences aspect of medical care, so Kissick and (Penn Social Science professor) Renee Fox taught us on policy issues. That was our first exposure in medical school to questions of health policy.”

“He also introduced preventive medicine in the Medical School and became the first chair of a new department then called ‘Preventive and Community Medicine,” said Schwartz.

Kissick’s interaction with, and influence on students in health-related studies across the campus was unusually broad, given that he was simultaneously a professor at Penn’s School of Medicine, the Wharton Business School and the School of Nursing.

Real-world policy making

“Bill was very interested in human development and loved to mentor young people who were at critical junctures in their lives professionally and personally,” said June Kinney, Associate Director of Wharton’s Health Care Management department. “He drew upon his Washington experiences in “wising up” his students with compelling stories and adages about how it really works in policy making.”

Looking back to his own student days, Sankey Williams, MD, now a Professor at Penn’s Perelman School of Medicine remembered what it was like to just be on the same campus where Kissick taught.

“His work in federal health care policy made him different from other campus experts on health care policy and research,” Williams said. “Knowing someone like him helped me and other students believe that people like us COULD change things that were important.”

Friends remember Kissick as a physically big man, a natty dresser who often walked with a near military swagger and a person with a clear sense of his own importance. Although he doesn’t appear to have been blinded by it. Despite the star quality conferred by his Medicare involvement, Kissick later looked back on that legislation and detailed its biggest mistakes. In his writings, he opposed a nationally centralized version of health care reform and instead, favored pushing control down to the states. That strategy, he said, would “constitute 50 natural laboratories for health care reform. Let the states individually devise innovations, struggle to implement them, learn from the experience, and then export the lessons to society at large.”

Early federal policy work

These concepts appear rooted in another 1960s project Kissick became heavily involved in shortly after he finished up with Medicare and became Director of Strategic Planning in the U.S. Surgeon General’s Office: writing the blueprint for the Regional Medical Programs (RMP) plan — a federally-funded program designed to improve medical care for the entire population by linking academic research with community health needs on a regional level. Launched in 1966, it was defunded and shut down by the Nixon Administration in 1976.

“Kissick’s involvement in big policy issues really included a lot more than just Medicare,” recalled Professor Schwartz. “His earliest exposure came when he worked for Luther Terry, the Surgeon General who in 1964 issued the landmark warning about tobacco and health. That was the most impactful action in the history of the Surgeon General’s Office and Kissick was there.”

John Kimberly, a Professor of Health Care Management at Wharton and Sociology at Penn’s School of Arts and Sciences, believes Kissick’s most significant impact was “encouraging students (and faculty) to think deeply about the intersection of medicine, business, and policy — where infinite needs and finite resources meet and where, as he would remind us all, compassion and economics are uneasy but inexorably joined bedfellows.”

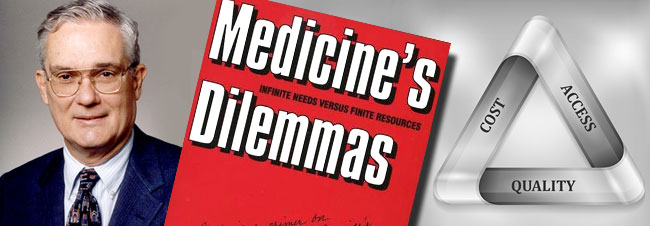

That theme — the quandary of infinite needs vs. finite resources — was a mantra throughout Kissick’s public remarks and writings. In 1994 it became the title of his book from Yale University Press,” Medicine’s Dilemmas: Infinite Need Versus Finite Resources.” The book, a deeply-thought personal narrative codified many of the “Kissickisms” for which he had become famous on campus.

Kissick’s ‘Iron Triangle’

The most important was his “Iron Triangle” theorem of the three competing elements that ultimately determine the true nature of the health care system: access, quality and cost containment. He said any one of the three can be improved — but only by compromising one or both of the other two. He pointed out that no society in the world has ever been — or will ever be — able to afford providing all the health services its population is capable of utilizing.”

For these reasons, he wrote, any U.S. health reform effort that hopes to succeed “must make choices. Must establish goals. Must determine trade-offs.”

One of today’s Penn faculty members who has adopted Kissick’s “Iron Triangle” concept is Lawton Burns, Professor and current Chair of Wharton’s Health Care Management Program.

“I used it every year in basically every presentation,” said Burns. “One thing all our MBA graduates around the world remember me for is ‘Kissick’s Iron Triangle.’ I was just in Beijing teaching this global modular course when one of our grads — who now heads up the Boston Consulting Group office in Shanghai — comes up to me says ‘Dr. Burns, are you still teaching the Iron Triangle?’ — and she graduated 15 years ago. So, Kissick’s legacy lives on globally and through the decades.”

At Penn, Kissick, who loved all things British, was an ardent fan of England’s National Health Service — the world’s largest publicly-funded single payer health care system. Each year, in LDI’s Colonial Penn Center auditorium, he gave a NHS lecture that became a beloved campus spectacle.

Pauly remembers the annual performance as “like good jazz: loud and sweet. The mortar would fall from the bricks when, dressed in bowler hat and carrying a furled bumbershoot, Bill called the House of Commons to order in a voice louder than the voice of God. His first maxim was that the NHS was one of the best health systems in the world but would be a disaster in the United States.”

Sound bite savvy

Aside from being an Anglophile, Kissick was a man of droll wit and sound bite savvy. Shortly after the Clinton health reform plan crashed and burned on Capitol Hill in 1994, he noted that health reform was a contact sport more like rugby than football: “The players have no helmets and no protective pads, run around in their underwear, and are in a constant state of terror,” he told the press. “The wounded are removed from the field of play and the game goes on uninterrupted.”

In another one that put a new spin on the words of 18th-century economist Adam Smith, he opined that “the invisible hand in the U.S. health care market is all thumbs.”

Although deeply enmeshed in the life and culture of Penn for more than three decades, Kissick remained closely connected to his alma mater, Yale. For six years, he served as a Fellow of the Yale Corporation — the 16-member board of trustees who oversee the university in New Haven. He was later awarded the Yale Medal for outstanding service to the school. And when he retired from Penn in 2001, he became an Adjunct Professor of Health Policy and Management, at Yale’s School of Public Health.

Kissick scholarships

At his 2001 retirement ceremony at Penn, Kissick pointed toward I-95 on which he would drive away from Penn for the last time and noted with pride one of the things he was leaving behind: The Kissick Scholarship Fund established by the Wharton Health Care Management Alumni Association (WHCMAA) — his former students — for their successors at Penn. Established in 1988 with funds provided by both Kissick and Alumni Association, the latest, 2013 award went to first-year MBA student Ross Stern.

In a second Kissick award program, LDI annually honors Penn students who have done meritorious research in the field of health services and policy with the LDI William L. Kissick Health Policy Research Award. The dual 2013 winners were MD/PhD student Nora Becker and MD student Morgan Sellers.

Hoag Levins is Editor of Digital Publications at the University of Pennsylvania’s Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics (LDI) and a former reporter and editor at newspapers and magazines in Philadelphia, New York and Washington, D.C.

Get the latest Penn LDI news, research, events, and opportunities.